(#83: 24 October 1970, 1 week)

Track listing: Atom Heart Mother: a) Father’s Shout; b) Breast Milky; c) Mother Fore; d) Funky Dung; e) Mind Your Throats Please; f) Remergence/If/Summer ‘68/Fat Old Sun/Alan’s Psychedelic Breakfast: a) Rise and Shine; b) Sunny Side Up; c) Morning Glory

At Tate Modern there is currently on display a group of audiovisual works by the late Brazilian artist Lucia Nogueira. Primarily a sculptor, she nevertheless worked across a range of fields, and her main work on show is a multiple TV diary of quiet, blowsy days in the fields and on the coast of Berwick-upon-Tweed. Nothing much happens but we are invited to contemplate the near-stillness, wonder how closely this overlaps with stasis or simply peace, and question the relevance or irrelevance of the kites and other subtly awkward paraphernalia which appear to exist both in and of themselves and beyond the earthly needs of the east Scottish-English border. There is monochrome greenness, and an uncommonly lucid sense of contentment, about these rovings.

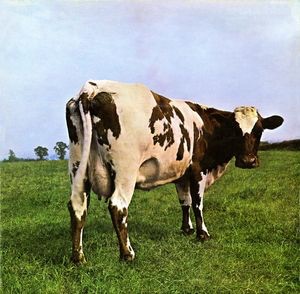

Similarly, the overwhelming impression gleaned by Atom Heart Mother is one of hard-won peace, although it displays its tightrope tentacles of impermanence more soundly than Nogueira. The notion of cover star Lulubelle III, and the complete lack of artist or other information without venturing into the gatefold sleeve, may have been inspired as a kind of antitode to Warhol’s cow wallpaper – also, coincidentally, on show at Tate Modern – but its apparent intent was to create the blankest yet brightest of empty spaces, ready to be filled in, the least psychedelic album cover ever created. Being Pink Floyd, however, it could not have helped but be the most psychedelic album cover ever created, and the existence of a three-piece suite with the word “Psychedelic” in its title at album’s end did not dispel this possible double irony.

There are vaguely sinister in-jokes in the Hipgnosis design – the cows veering menacingly towards us on the rear may be a simple pun on “group shot,” but the 1994 CD remastering and repackaging of the record joins a few more vowels to their attendant consonants; now there are pictures of pig stools, resembling a concentration camp, a snorkelling diver (that aqueous release/return to womb scenario again), a hard-hatted man climbing up to the top of nobody’s idea of a fat old sun (an atomic plant which could erase everything else seen and heard on the record), a psychedelic breakfast sculpture reminiscent of the Swiss artists Peter Fischli and David Weiss (they too are to be seen at Tate Modern), and a pair of apparently genuine recipes as “Breakfast Tips” for Alan, one of which describes a “Traditional Bedouin Wedding Feast” involving the successive stuffings of chicken into lamb into goat into camel, and the other of which, in German, gives a recipe for a cow brain delicacy as an alternative to scrambled eggs.

Of Pink Floyd themselves there is as little as possible on Atom Heart Mother – that title, pointing back to their blues roots or preparing to breathe their natural last? – but then they wanted the freedom from being “Pink Floyd,” to employ and address as many musical styles as they felt able and willing to do. The members’ attitude to the record over the years has been ambivalent; sometimes they laughingly dismiss it, at other times they solemnly praise it.

As with most of the rest of Floyd’s work, you are invited to make of it what you can. Alternatively you may listen to the fifty-two minutes of Atom Heart Mother – or forever, if you have the LP edition and listen to Alan’s tap dripping for eternity in its locked groove – and wonder exactly from what, or whom, Pink Floyd were hiding, or running away. They are perhaps the most elusive act in this tale; they only directly appear five times, and none of the number ones is immediately obvious. Moreover, their two most famous albums – three, if you count the first one, as you must - make no appearance in this list at all. Somehow they simultaneously place themselves above and below such inconvenient matters as record rankings, and possibly life itself.

But then a record such as Atom Heart Mother could only have reached number one in a time when all options, both aesthetic and political, were open; I am uncertain whether it is quite as unlike anything we’ve previously documented in this tale as I sometimes thought, but at the same time there really is nothing like it anywhere in this story. This was the age when the jazz, R&B, classical and Mod/psychedelia strands of British music were colliding and colluding in fluorescent colours, frequently with the equivalent American strands, thanks to Miles Davis, Carla Bley, Christian Wolff and other honest brokers; AMM once shared management with Syd Barrett’s Floyd and more than once supported them in concert, and the Keith Rowe influence can be heard directly on the more outré moments of “Interstellar Overdrive,” especially the full-length version to be found on the Tonite Let’s Make Love In London soundtrack album.

That influence, together with the more general influence of Pepper, spoke directly to Bley, and the Phantom Music moments on Escalator Over The Hill in particular owe virtually everything to both. Thanks to enthusiastic youngsters undetained by the noose of tradition such as Robert Wyatt and Keith Tippett, the scenes crashed into each other here; Westbrook, Gibbs and Surman were one step away from being pop stars, the Brotherhood of Breath breathed fiery Kwela life into everything, and Tippett’s Centipede mopped up most of the central field players – King Crimson, Nucleus, the South Africans, Patto and especially Soft Machine – into a glorious, glutinous (tone) row. Dudu Pukwana collided with Richard Thompson, the Incredible String Band fed back their own otherness, and somewhere from where Cornelius Cardew had set off, the Scratch Orchestra, featuring the young Eno, Bryars and Nyman among incendiary others, were busy demolishing every tower for every greater good.

Thus it was a rare season for Pink Floyd, but were they venturing into the field, or sitting aside from it, or departing for their own pastures? As great as Atom Heart Mother is, I can’t help but think that the Philip Jones Brass Ensemble, Ron Geesin, the John Aldiss Choir and Alan Stiles’ frying bacon and eggs are all covering up for an unbridgeable absence. The Floyd had expertly avoided the irritating question of how exactly to reconstitute themselves for some time following Barrett’s imposed absence; A Saucerful Of Secrets saw them gingerly venturing out from the ashes of Piper At The Gates Of Dawn but Syd was still technically in the group and his concluding “Jugband Blues” seems to bring the rest of their adventures down with him. Ummagumma was a double, half-live band performance, half-studio solo projects, and although I love it dearly and the live tracks, recorded at Birmingham University – were the Sabs in attendance? - are particularly incendiary, the trope of playing for time is unavoidably in its centre.

Then the various film projects, and Atom Heart Mother itself, a final plea for space to breathe and regroup. They don’t quite know where they’re going – yet – and the side-long title track offers no clear directions other than there is clearly some unfinished 1967 business to clear up. Given the presence of the Abbey Road studios and the epic, discursive nature of the record’s big setpiece, there is more than an indication that the Floyd intended to take up from where the Beatles had left off.

Less assured of their constructive skills as composers, however, the group drafted in Ayrshireman Ron Geesin, sound designer and general odd-job avant-garde art music man, to help out with the orchestration and construction of the “Atom Heart Mother” suite. Geesin had already worked with Roger Waters to startling effect on the Music From The Body soundtrack, although from the suite’s twenty-three or so minutes it would if anything appear that Pink Floyd are trying to bury themselves under Geesin’s flashy picture show.

Throughout the piece the brass and choir are the most prevalent and noticeable factors; they more or less direct the work’s progression and divert it into its most adventurous digressions. I will not waste time debating where the various sections of the piece begin and end, since that is in part a red herring and the piece is meant to be listened to as an integrated whole. Still, it begins with a slowly-fading in drone – just like the body of Escalator – with a hiss of processed cymbals giving way to forthright brass figures issuing Harrison Birtwistle-esque polytonal fanfares. The group eventually smack themselves into the track’s wakefulness, only to be answered by a chorale of squealing brakes and crashing cars.

This gives way to a lugubrious organ and ‘cello melody, vaguely reminiscent of Messiaen but far more in keeping with the poignant, Klezmer-derived chord progressions of mourning one finds in the work of Bley, Wyatt, Kurt Weill and so forth. Air raid sirens – the war, again, and more achingly in the Floyd’s work than anywhere else in the seventies – rise up to David Gilmour’s first guitar solo, partly “Sleepwalk” but mostly Hank Marvin, then becoming louder and more anguished. At its climax the brass re-enters, followed by the choir, and then relative peace reigns again for an organ/choir interlude, giving a curious resonance of the cowboy trail of fifties childhoods.

The choir figures then increase serially in polytonality and thickness of texture before finally going into atonality. Nick Mason’s drums herald the suite’s main theme, Godspeed You Black Emperor! come immediately to mind and the choral lines inspire thoughts of the George Mitchell Minstrels having a go at Peter Maxwell Davies. Quite unexpectedly, the piece then diverts to the land of the Peddlers; working men’s club bass and organ. Gilmour’s solo here pays due tribute to BB King – astonishing how one can scratch the surface of so many guitarists around this time and find Hank Marvin and/or BB King just beneath – before Mason’s drums turn impatient, Gilmour’s guitar slips out of focus, a Moog hovers into view and we are suddenly in the world of porno-funk.

With perhaps a nod to Jean-Claude Vannier’s arrangements for Gainsbourg’s Melody Nelson, while nodding slightly in the direction of Stockhausen’s Stimmung, the choir moves into abrupt bursts of spoken, pointillistic, not-quite-comprehensible non-language (was Celentano listening?). This is, let us remind ourselves, being played out on side one of a number one album.

Then the piece switches majestically to the major key. Mason’s pregnant tick-tock rimshots play against cinematic brass. But then we return quite decisively to unfinished 1967 business; a tortured, tonally distorted inversion variant on the “Strawberry Fields”/”Walrus” Mellotron figure takes centre stage, surrounded by space debris of cut-up speech, sound effects and sighs of atonality. This all builds up to a tremor, which thence becomes an explosion, before moving back down to quietude. “Silence in the studio!” someone barks. The group moves back to the main theme, then back to the organ/’cello unisons, and finally Gilmour’s swooning Hank guitar which then doubles up in agony. The brass returns but is looped out of rationality (this could almost have played as a requiem for Hendrix). Again we hear the brass/choir theme before the band works the piece up towards its climax. After a slight nudge out of tonality in its penultimate chord, we get one final, suspended-out-of-tonality pause, and then a mighty E major – that 1967 chord that simply won’t go away.

After that it is left only for the individual group members to give their own thoughts. “If” is Roger Waters’ contribution and I doubt whether I’ve ever heard him sing so quietly – as though afraid to sound louder than the minimally plucked acoustic guitar – or as less like Roger Waters than elsewhere; sometimes he sounds like Elvis, or even Cliff, in ballad mood but the poignancy is too much; he is talking directly to the absent man, the man who could have done everything that it took a brass section, a choir and Ron Geesin’s sound effects library to accomplish with one fuzz pedal and a handily-positioned screwdriver. To hear him whisper, or whimper, “If I go insane/Please don’t put your wires in my brain” is almost unbearable – and Gilmour’s keening guitar in the distance only adds to the grief – until you realise that he’s basically trying to sound like Syd. Not yet absent from the world – he spent 1970 recording his second album and still gamely trying to make a go of things – his absence from Atom Heart Mother is all pervasive. Mason’s ride cymbal cuddles in gently on the fourth verse, and then deep piano and “In The Ghetto” guitar cries fill the picture of absence (“And if I were a good man/I’d talk with you more often than I do"). Did someone say the Beatles?

“Summer ‘68” is Richard Wright’s song, and while vocally he does sound a little like Harrison, every atom of the tune seems to want to hark back to the days just spent, from its bright, Brill Building piano intro, its “When I’m 64” paraphrase (“Perhaps you’d care to state exactly how you feel”), the rumbling down of the organ and roaring up to launch into a “Baby You’re A Rich Man” pastiche (“How do you feel?”), the “Penny Lane” trumpet figure, everything points to the Fabs. Some vocal fugues give way to a drift into the minor key, led by Wright’s piano. Then Geesin’s brass re-enter, as per “A Day In The Life.” Gilmour’s acoustic guitar slows the song down, hesitantly, to a waltz. A bright minor key brass coda finishes the song off – and it is superficially a song about one more lay on the road; but who is this “Charlotte Pringle” who surfaces so menacingly towards the song’s finale? Again I can’t shake off the thought that this is still about missing Syd.

Then again, Gilmour’s voice on his “Fat Old Sun” is also as unlike any other David Gilmour vocal I’ve ever heard; if anything he sounds as though he’s trying to be McCartney, and this peaceful interlude with its unexpected tonal shift (at the phrase “a tongue so strange”), Mason’s stumbling, homemade drums and the whirling dervish of unattributable guitar noise in the far distance (together with decidedly non-tonal keyboards) would scarcely have been out of place on McCartney’s own rural adventures of the period. But Gilmour’s repeated cry of “Sing to me, sing to me” is moving in a sense purely its own; we know the voice he is avidly, painfully seeking.

Then Nick Mason has the final word with the thirteen-minute “Alan’s Psychedelic Breakfast.” The dripping tap serves as a rhythm as Alan – not engineer Alan Parsons but band roadie Alan Stiles – sleepily stumbles and grumbles his way into the kitchen to rustle up something, perhaps out of the cows we are admiring on the sleeve. “Marmalade, I like marmalade,” he pronounces. E major fanfares give way to a sampled beat of knife scraped against toast – singular events like “Revolution 9” notwithstanding, is this the first piece of music in this tale to deploy loops and samples? – before two pianos filter in and out of each other and the scene gives way to a bright, skipping Chris Rea roundelay of piano and guitar, although again there is the whirling ghost of Syd’s guitar impersonating, or blending with, the kettle. Acoustic guitar plays bucolically as eggs and bacon sizzle on the cooker, like scratched 78s. Electric guitar and bass join in while Alan’s comments wander into a loop. Then piano and drums, joined by the full band, launch into an immediately familiar mid-tempo pace which does seem to set the scene for their greater subsequent triumphs. Alan’s voice is interspersed with the meditations, and the piece arrives at something resembling a climax. Wright’s piano provides a florid Liberace sign-off and the tap drips forever – or is that the clock ticking, counting down towards nothingness?

A nice day out in the country. Manipulating beauty and other things into things which they might not be. Following the dank urban hell of Paranoid we are offered the bright, green, shiny, yellow alternative; get back to the land, get back home, back to those spaces for which the rest of 1969 and 1970 had been yearning, back to rediscover who we, the Pink Floyd, really are, whether we can still count, and what the hell do we do from hereonin. I’m not convinced that they have ever really escaped that original fugitive ghost – indeed its memory was the principal power behind their most momentous works – but rejoice at a time when something this adventurous (especially since it was pretending to be as unadventurous as possible) could, even if only for one week, outsell everything else, and maybe make some moves towards it happening again.